It feels like everyone and their aunt is making AI / AR smart glasses nowadays, especially as someone who tests the best smart glasses around. But something caught my eye when reading a description of Brilliant Lab’s new Halo glasses – as with their long-term memory capabilities, they promise to remind you of details of conversations and objects you’ve seen “years or even decades later.”

In real-time, Brilliant Labs’ specs can apparently offer contextual information based on what it hears and sees, too. This style of assistive help in the moment and later on sounds like a more ongoing version of features like the Ray-Ban Meta glasses’ visual reminders, features that Meta and others have said they plan to make (or have already made) an optionally always-on tool.

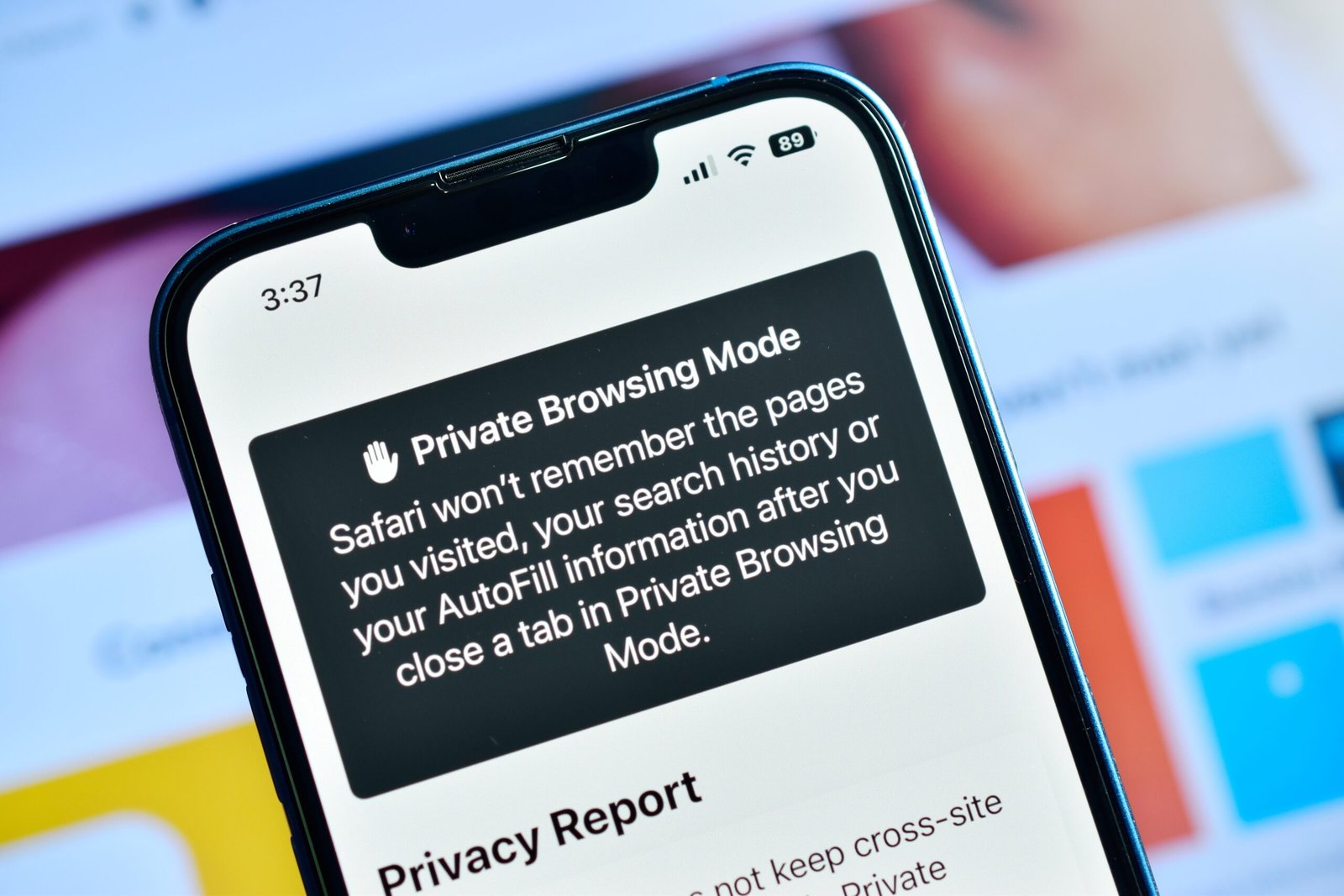

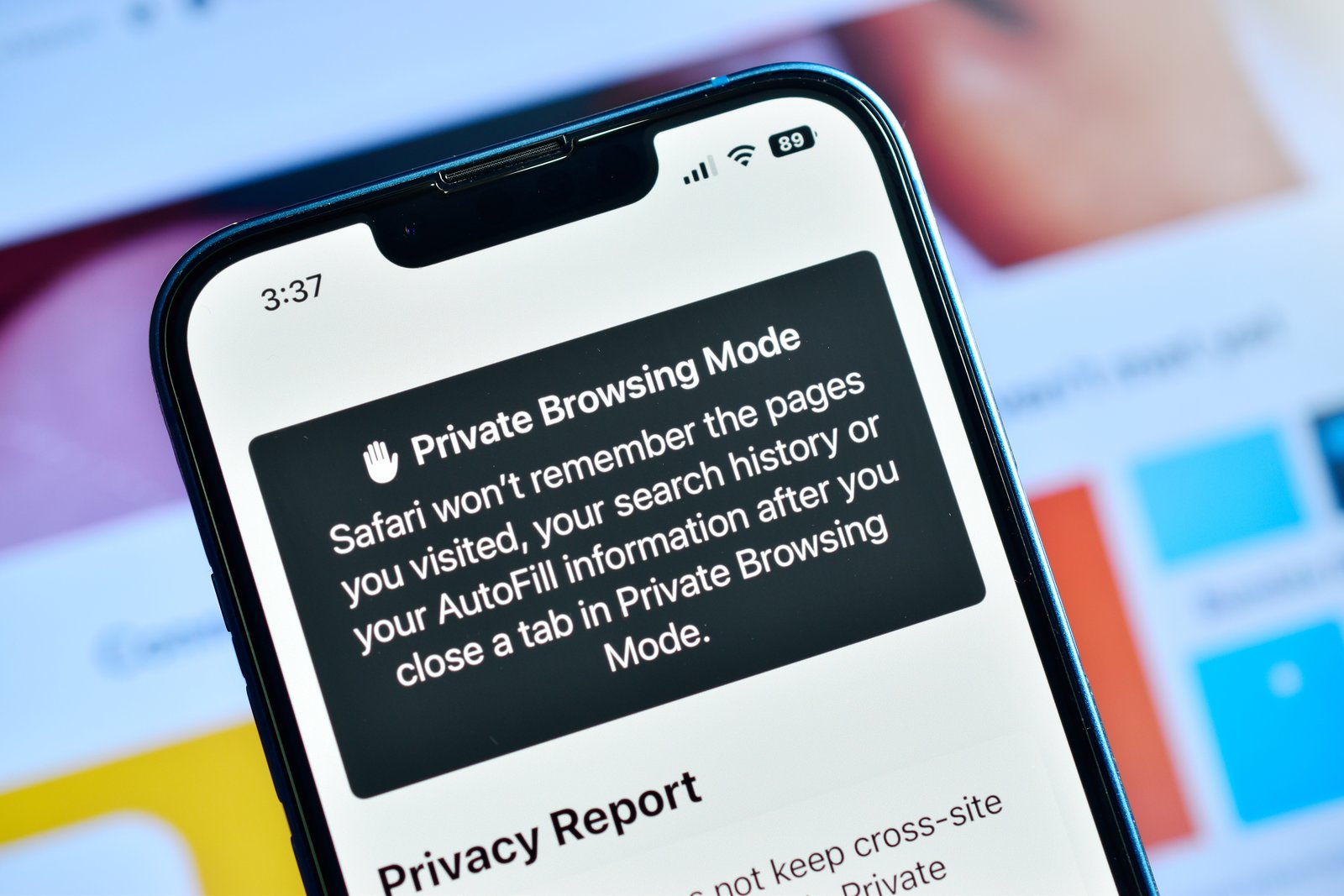

Now, Brilliant Labs has said its agent Noa will serve as a sort of AI VPN. Like a VPN reroutes your data to keep your online activity more private, Noa promises to offer similar levels of privacy as it communicates with the AI model powering its cognitive abilities.

Other Halo highlights are its “world’s thinnest AI glasses” design, its built-in display that sits in your periphery like some other AI specs we’ve seen announced this year, and it will have a relatively affordable $299 asking price (around £225 / AU$465) when it launches in November.

But even as someone who loves my Ray-Ban smart glasses and can see the benefits of these Halo glasses, I’m worried these smart specs are a sign we’re continuing to race towards the death of privacy.

Risk vs reward

Smart glasses wearables with cameras are already, admittedly, something of a privacy conundrum. I think the Meta Ray-Ban specs do it well – only letting you snap pictures or short videos (or livestream to a public Meta account on Facebook or Instagram), and have an obvious light shine while you do so.

But the next generation of utility wants to boast an always-on mentality – cameras that activate frequently, or microphones that capture every conversation you have.

This would be like the Bee wristband I saw at CES (which Amazon recently bought), which promises to help you remember what you talk about with detailed summaries.

You can instantly see the advantages of these features. An always-on camera could catch that you’re about to leave home without your keys, or remind you that your fridge is getting empty, and Bee highlighted to me that you could use it to help you remember ideas for gifts based on what people say, or recollect an important in-person work chat you might have.

However, possible pitfalls are close behind.

Privacy is the big one.

Not just your own, though you’re arguably consenting to AI intrusiveness by using these tools, but the privacy of people around you.

They’ll be recorded by always-on wearables whether they want to, or even know they are, or not.

Privacy makes up a big part of media law training and exams that qualified journalists (like me) must complete, and always-recording wearables could very easily enable people to break a lot of legal and ethical rules. I expect that without these people necessarily realising they’re doing something wrong.

Move fast and break everything

Big tech has always had an ask for forgiveness mentality. Arguably, because time after time, punishments (assuming they are even punished) are usually vastly outweighed by the benefits they reaped by breaking the rules.

This has seemed especially true with privacy, as our data seems to get mishandled by a company every other month – in small, but also sometimes catastrophic ways.

I’m looking at you Tea.

We’ve also already seen examples of AI companies playing fast and loose with copyright, and I expect the rulelessness will only get worse in the AI space as governments across the globe seem less than keen to properly regulate AI so they don’t hamper their country’s efforts to win the digital arms race.

AI wearables capturing every moment of our lives (from multiple angles to boot) with video and audio are a catastrophe waiting to happen.

Yes, there are always promises of privacy, and optional toggles you can switch on to supposedly enhance your data protection. Still, for every good actor that keeps its privacy promises, we can find plenty of companies that don’t – or quietly change them in new ToS you’re asked to sign.

We can hope that robust regulation and proper punishment for malpractice might come in and help avoid this disaster I foresee, but I’m not holding my breath.

Instead, I’m coming to terms with the demise of privacy – a concept already on its last legs – and accepting that while Big Brother might look different from how George Orwell pictured it, it will (as predicted) be watching us.